Why patient engagement must come first in rare disease trials

For the millions of people living with a rare disease,1 a clinical trial can offer the brightest glimmer of hope. Yet the path to translating clinical trial progress into treatment breakthroughs can be difficult, which can erode trust in these communities. As Rare Disease Day draws near, this month we reflect on a critical truth – successful rare disease trials are not built on scientific ambition alone. They are built on a foundation of genuine patient engagement, designed around the realities of patients' lives.

The unique challenges of rare disease trials

Developing treatments for rare diseases presents a unique set of obstacles. The patient populations are, by definition, very small and often geographically scattered,2 which makes recruiting enough participants for a study a significant hurdle from the very start.

But there is also a profound human element that needs consideration. Patients and their families carry a heavy emotional burden, navigating diagnoses that few understand. Many face a long, frustrating journey to reach the right diagnosis, often experiencing multiple misdiagnoses and enduring treatments that provide little or no relief, further eroding trust in mainstream healthcare.3,4 Asking them to participate in a trial adds another layer of complexity. The burden of travel to specialist sites, time away from work and/or school and support systems, demanding schedules, and invasive procedures accumulates quickly.5 The strain of participation is more than just a logistical issue; it's also an emotional and financial one.

Where rare disease trial design can evolve

Patient engagement is especially critical in rare diseases research, yet it is often introduced later in the trial-planning process. This leads to study objectives, designs, and requirements that do not meet the needs of participants. Patients and families are often the true experts in their condition, with deep experiential knowledge that can meaningfully inform trial objectives and goal setting. If participants are brought into the conversation earlier, there is greater opportunity to shape protocols that reflect the realities of living with a rare condition and to enable meaningful, practical input.6

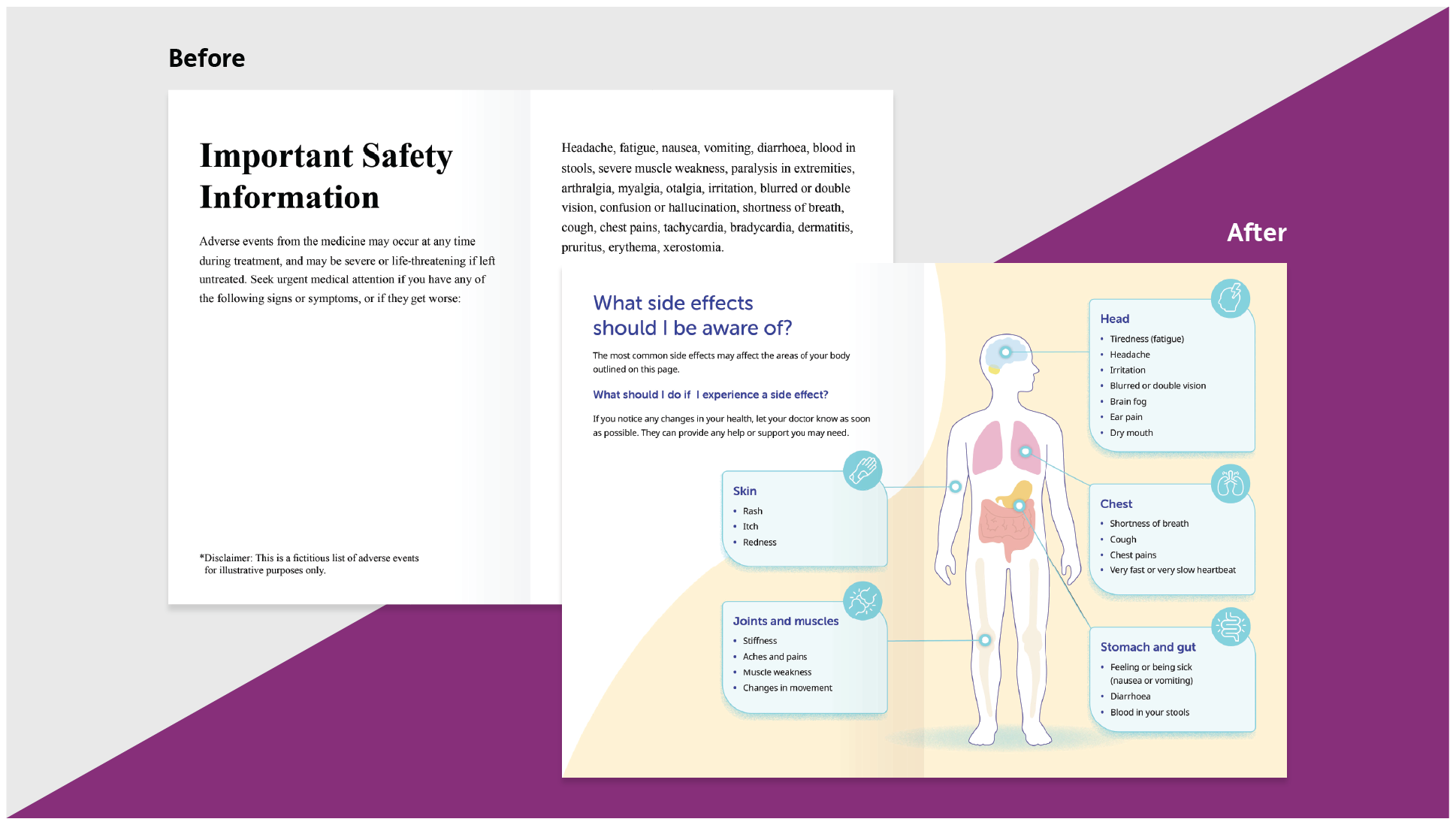

Although regulatory requirements must be met, translating complex scientific information into language that is understandable for non-scientists is particularly important in rare disease communities, where highly knowledgeable patients and caregivers may still face information overload. For example, interviews with people living with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis revealed that the volume and complexity of information can make clinical trial material difficult to understand.5 Clear communication supports confidence, trust, and informed participation.

Rare disease trials also present a unique opportunity to more fully recognise the crucial role of caregivers. Caregivers are deeply embedded in the patient journey – managing logistics, interpreting information, providing emotional support, and frequently influencing participation decisions. Thoughtfully considering their needs, capacity, and insights can strengthen engagement and improve the overall trial experience for both patients and families.

Designing trials in this context requires careful, practical consideration of how studies are structured, communicated and delivered - not just scientific intent.

What meaningful patient engagement looks like in rare disease trials

True patient engagement starts early and is woven into the very fabric of the trial design. In practice, this often comes down to a small number of critical questions: when and how patients are involved, how participation burden is assessed, how information is shared, and whether caregivers are actively supported as part of the trial journey. While established patient groups provide crucial input, meaningful engagement also requires looking beyond these pools to hear wider perspectives. Actively reaching out to underrepresented communities ensures that these foundational questions are answered in a way that reflects a more complete spectrum of experiences, shaping whether engagement is truly meaningful or merely symbolic.

To support this kind of practical decision-making, we’ve captured these engagement considerations in a short, practical checklist to help teams translate patient-centred principles into trial design decisions.

This mindset prioritises clear, empathetic communication. It means replacing jargon with plain language and ensuring families feel heard and respected throughout the process. It’s about designing for feasibility, not perfection. A slightly less ambitious trial that retains all its participants is far more valuable than a "perfect" one that no one can complete.

Why this matters for trial success

A patient-first approach not only addresses the inherent challenges of rare disease research but also directly impacts trial outcomes. When we put patients first, everyone benefits.7 A trial designed with patient realities in mind is more likely to meet its recruitment goals. Participants who feel understood and supported are far more likely to remain in a study, enabling the collection of high-quality data.

Most importantly, it builds trust. By demonstrating a genuine commitment to the community's well-being, we forge long-term relationships that extend far beyond a single study. Trust then becomes the bedrock for future research and innovation.

References:

- The Lancet Global Health. The landscape for rare diseases in 2024. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(24)00056-1/fulltext. Accessed January 2026.

- Boulanger V, et al. Pharmaceut Med. 2020;34(3):185–190.

- Bruce IN, et al. Lupus Science & Medicine. 2023;10:e000856.

- Lupus UK. Research in the news – The impact of misdiagnosis. Available at: https://lupusuk.org.uk/2025/03/03/research-in-the-news-the-impact-of-misdiagnosis/. Accessed February 2026.

- Frost J, et al. Health Expectations. 2025;28: e70260.

- Gaasterland CMW, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14:31.

- Gobat N, et al. Lancet Glob Health. 2025;13(4):e716–e731.